Seeking aid abroad, Lebanon uproots Syrian refugees

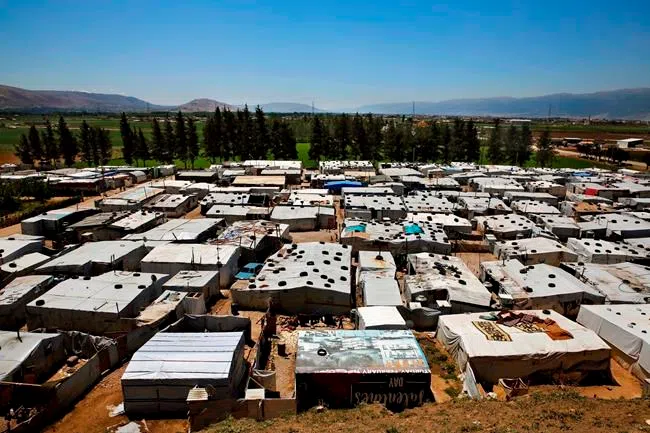

BEIRUT — Three years ago, Ahmad Mohsin was forced to relocate his campsite in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley after soldiers raided the community of Syrian refugees where he lived and smashed their belongings. The message was clear, he said: they were not wanted.

On Tuesday, Mohsin, 39, was preparing to break down his camp again, after an order came from the security services to move once more.

Even as donor nations raise money for Syria’s neighbours to host refugees of the country’s civil war, a leading international rights group and the U.N.’s refugee agency say Lebanese authorities are evicting refugees from towns and camps in the country on questionable legal grounds.

Mohsin, from Syria’s third largest city Homs, said on the second order to move he went to a local official to ask for help.