At what point does crying ‘lynching’ trivialize the word?

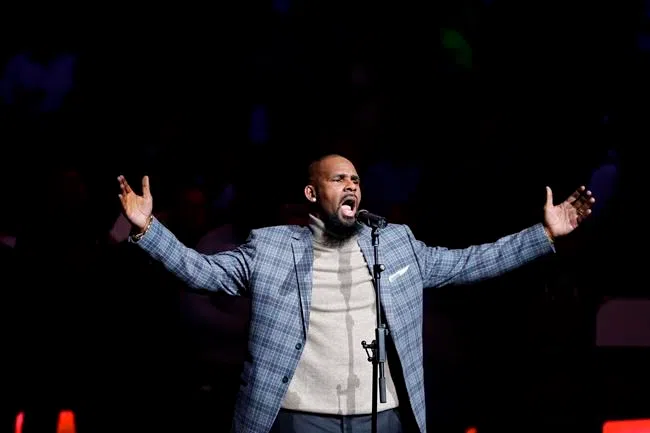

WASHINGTON — R. Kelly says boycotting his music because of the sexual abuse allegations against him amounts to a “public lynching.” Bill Cosby’s people say his conviction was a lynching, too. Kanye West, in trying to defend his inflammatory comments about slavery, has been tweeting lynching imagery to assure fans he won’t be silenced.

The tactical use of lynching references over the past few days by celebrities under fire is generating disgust among historians and others who have studied the ghastly killings and mutilation of thousands of black people in the U.S. in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Demeaning” and “reprehensible” were some of the terms used by those observing the use of lynching metaphors, which seems to be happening more often and crossing racial lines.

“It detracts and it takes away from the historical significance of what happened, because there are no comparisons to the way it’s being used today and the reality of lynch mobs,” said E.M. Beck, a retired University of Georgia professor and co-author of “A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings 1882-1930.” ”I think it is demeaning to the people who were lynched, and I think in some ways it might be considered to be demeaning by the descendants of those people.”