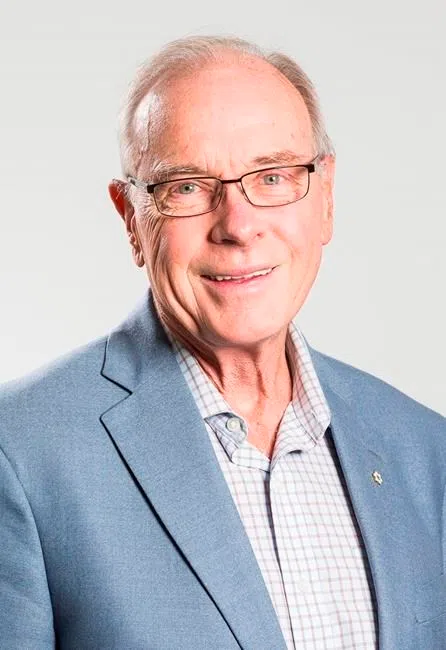

Frank King, who brought the 1988 Winter Olympic Games to Calgary, dies at 81

CALGARY — Frank King, one of the architects of the Calgary Winter Olympics in 1988, has died at the age of 81.

King was the chief executive officer of Calgary’s organizing committee. King and Bob Niven brought a Games to Calgary that changed the face of the city and helped make Canada a powerhouse in winter sport.

An avid runner who competed in Seniors Games, King died Wednesday of a heart attack while training at a downtown club, according to Niven.

King and Niven were both members of the Calgary Booster Club in 1978 when the club president asked if anyone was interested in bringing a Winter Olympics to the city.