Canada’s emergency alert system can’t measure how many phones get the notices

OTTAWA — The federal government says it can’t measure how many people actually receive emergency-alert messages on their phones.

The Alert Ready system is designed to notify Canadians of potentially dangerous situations — everything from terrorism and explosions to flash floods and tornadoes. It is also the system used to broadcast Amber Alerts when a child goes missing.

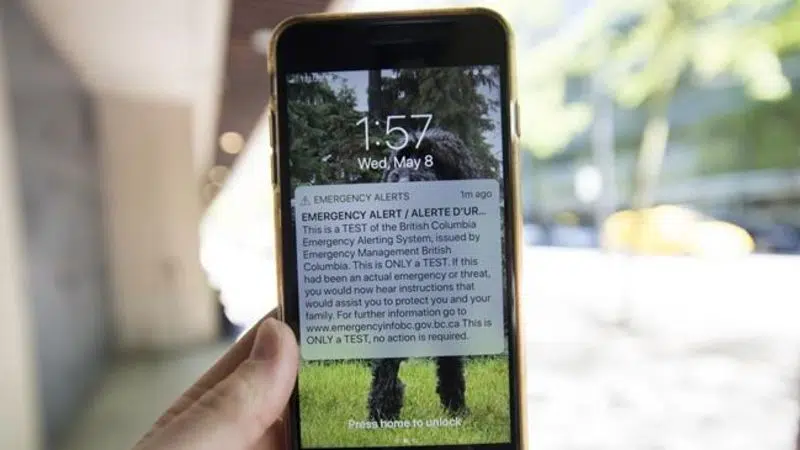

Public Safety Canada spokesman Tim Warmington said that during the most recent test of the system, conducted May 8, alerts “were successfully processed and distributed” without issue, but acknowledged there is no way to know how many people received them.