Warm weather forces city in Quebec to cancel ice-fishing villages for first time

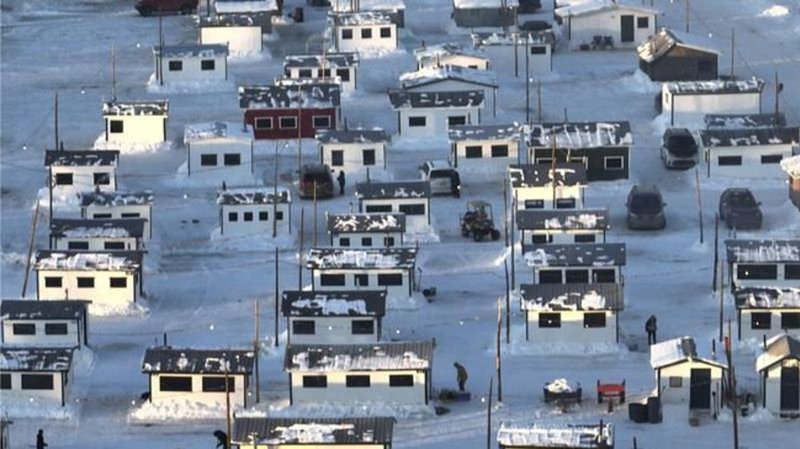

SAGUENAY, Que. — There will be no colourful ice-fishing huts dotting the frozen water near Saguenay, Que., this year after mild winter weather forced authorities to cancel the popular tradition for the first time.

The municipality about 200 kilometres north of Quebec City announced last week that the ice wasn’t thick enough to open the fishing villages at Anse-à-Benjamin and Grande-Baie, which normally feature hundreds of huts and cabins that are popular with tourists and locals alike.

The news was a huge shock and disappointment to people in the area, according to Rémi Aubin, who is president of a local fishing group.

“Ice fishing for the people of the Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean region is an activity that is not only recreational and economic, but also part of the culture of the people here,” he said.