Alan Kurdi photo left Canadian government scrambling, emails reveal

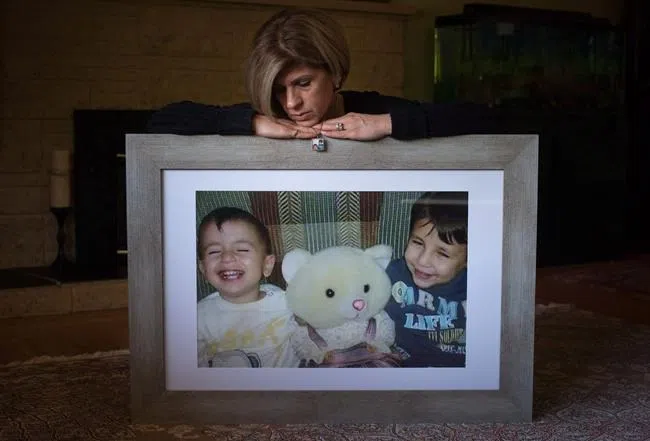

OTTAWA — In the hours and days after three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi’s lifeless body washed up on a beach in Turkey, Canadian immigration officials were focused on fashioning and tweaking their formal responses — words that ultimately rang hollow as the world mourned the little boy’s death.

New documents obtained by The Canadian Press through the Access to Information Act provide a revealing look at the often-frantic flurry of internal government communications that erupted in the days after a heart-rending photo of the toddler’s corpse rocketed around the world.

The email trail reveals federal staffers grappling with the painfully slow wheels of bureaucratic red tape as they try to respond to a torrent of media requests, all the while fussing with the minutiae of wording government statements that did little to address the most burning questions.

The Canadian Press requested all emails dealing with the subject Syrian refugees that were received and obtained by David Hickey, then-director general of communications for the federal Immigration Department, for the three days following the death of Alan Kurdi.