From prison to politics: Chelsea Manning runs for US Senate

NORTH BETHESDA, Md. — Chelsea Manning is no longer living as a transgender woman in a male military prison, serving the lengthiest sentence ever for revealing U.S. government secrets. She’s free to grow out her hair, travel the world, and spend time with whomever she likes.

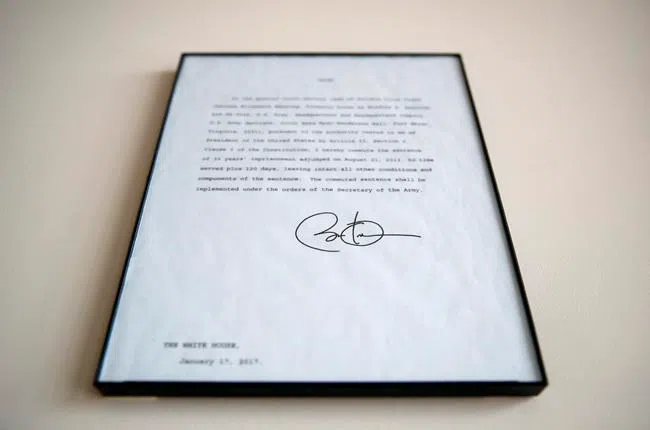

But a year since former President Barack Obama commuted Manning’s 35-year sentence, America’s most famous convicted leaker isn’t taking an extended vacation. Far from it: The Oklahoma native has decided to make an unlikely bid for the U.S. Senate in her adopted state of Maryland.

Manning, 30, filed to run in January and has been registered to vote in Maryland since August. She lives in North Bethesda, not far from where she stayed with an aunt while awaiting trial. Her aim is to unseat Sen. Ben Cardin, a 74-year-old Maryland Democrat who is seeking his third Senate term and previously served 10 terms in the U.S. House.

Manning, who also has become an internationally recognized transgender activist, said she’s motivated by a desire to fight what she sees as a shadowy surveillance state and a rising tide of nightmarish repression.