Will claims of illegal party financing sink Charest’s hopes of political comeback?

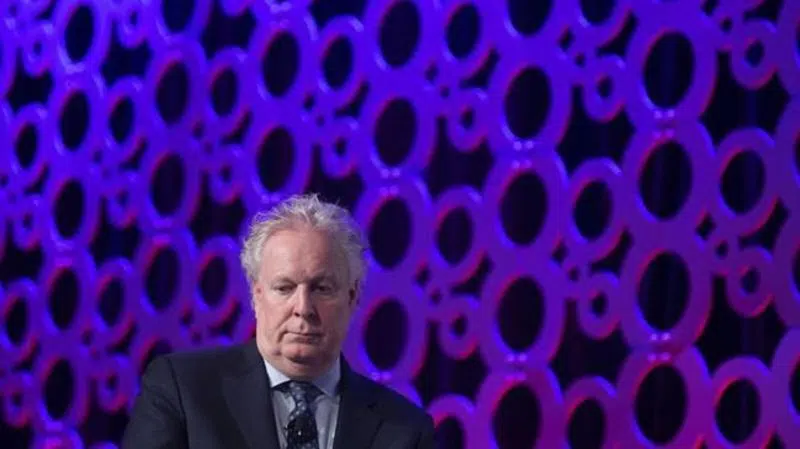

MONTREAL — While former Quebec premier Jean Charest mulls a leadership bid for the Conservative Party of Canada, recently unsealed police warrants have given his political opponents plenty of ammunition.

Charest, Quebec premier from 2003-12, and before that a federal cabinet minister and leader of the Progressive Conservatives, is seen as a well-known, experienced, bilingual and talented politician who can unite English and French Canada.

But he carries serious political baggage. He’s been under investigation since 2014 by Quebec’s anti-corruption unit for sitting atop the provincial Liberals while the party allegedly ran a pay-to-play scheme involving some of the biggest construction companies in Quebec.

And police warrants unsealed Thursday contain detailed affidavits from major construction industry officials who said they donated to the Liberals during Charest’s tenure, and that they felt pressured by the party’s top fundraiser to give money or risk losing influence with the Liberal government.