Schools face daunting, unique reopening challenges during pandemic

As Canada begins grappling with the issue of recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the question of how to safely reopen schools has emerged as a particularly thorny topic. Physical constraints, economic considerations and student needs and habits all seem at odds with public health advice which mandates rigid physical distancing for the foreseeable future. How can schools adapt to the new reality? Some design experts weigh in:

Are today’s schools well-positioned to respond to situations like this?

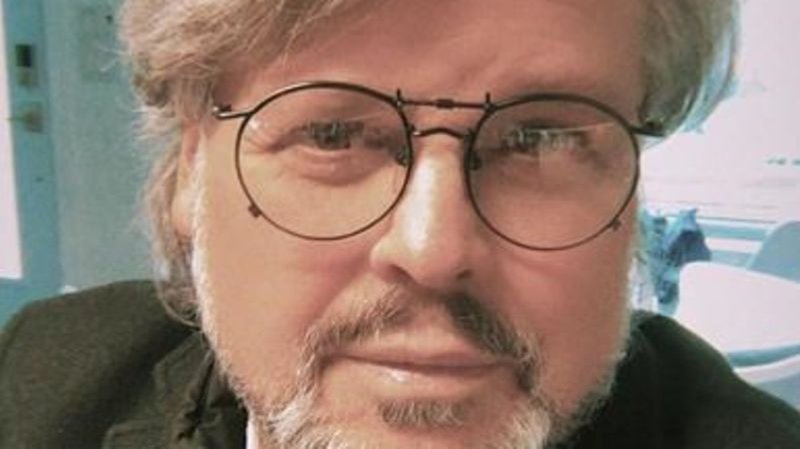

No, at least in most cases. Paul Sapounzi — managing partner with the Ventin Group architects, who have been designing educational spaces since the 1970s — said school construction projects have been largely driven by economic rather than public health concerns for decades. In Ontario, for instance, builders work with a strict formula that allocates about 9.2 square metres per elementary-school student and 12.1 square metres per high-school student. Sapounzi said such formulas, which are similar across the country, result in classrooms crowded with upwards of 30 pupils apiece, particularly in urban settings.

“We were trying to create the densest school possible for the least amount of money,” he said of past practices. “It’s going to be the opposite of that going forward. We need to be based on the ability to adapt easily to possible economic and health disruptions.”