Judge calls for release of evidence in wrongful murder conviction of N.S. man

HALIFAX — Key evidence explaining what led to the wrongful murder conviction of a Nova Scotia man who spent almost 17 years in prison should be released later this month, a senior judge decided Tuesday.

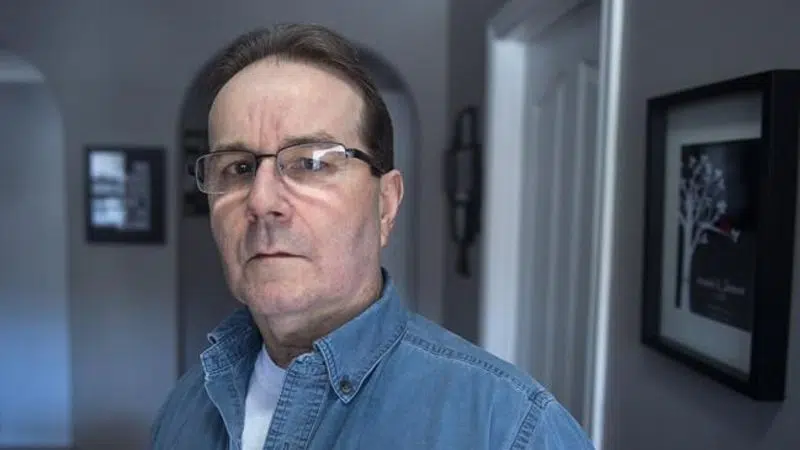

The Canadian Press, CBC and the Halifax Examiner had asked Justice James Chipman for access to federal documents that include details of how 63-year-old Glen Assoun was improperly convicted of second-degree murder on Sept. 17, 1999.

On March 1, 2019, after a two-decade struggle by Assoun to overturn his conviction, a judge found him innocent in the 1995 stabbing death of 28-year-old Brenda Way.

Canada’s justice minister has already declared there was “reliable and relevant evidence” that wasn’t disclosed during the criminal proceedings.